Hadith: “The one most eager to issue fatwas among you is the one most daring in casting himself into the Fire.”

اَجْرَؤُكُمْ عَلَى الْفُتْياَ اَجْرَؤُكُمْ عَلَى النَّارِ

Explanation: When clarifying religious rulings, caution is essential. One must not presume to issue legal opinions—nor publish writings on such matters—without proper knowledge.

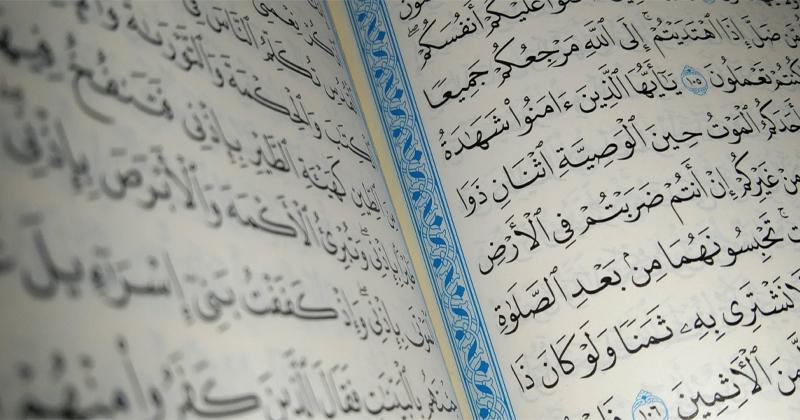

The one who inquires about a ruling is referred to as the sa’il or mustafti , while the one who responds with a ruling is known as the mufti , and the ruling itself is called a fatwa . Certain conditions must be met in these interactions. A person should ask about religious matters solely to learn and act upon the truth—not to use the answer as a weapon against others, expose someone’s ignorance, or spark unnecessary argument.

As for the one who answers, their burden is far heavier. For they assume a task of grave responsibility before Allah. To give a ruling without grounding it in authoritative religious sources is a reckless act, a false claim in the name of Islam, a violation of the sanctity of the sacred law, and an offense against the dignity of the Muslim community.

A person should occupy himself with what concerns him and refrain from speaking on matters he does not fully understand. Otherwise, he will not escape the spiritual weight of his words.

Sadly, in our time, few uphold this vital principle. There are many who, despite lacking proper knowledge—or possessing only a superficial grasp—do not hesitate to write or speak on serious legal matters, posturing like mujtahids. They are quick to label any disagreement with their views as ignorance. Yet, in the past, even the most learned scholars, masters of the religious sciences, dared not engage in independent reasoning ( ijtihad ) or issue personal rulings. They adhered instead to the well-established interpretations of trusted imams like Imam al-Azam, Imam Malik, and others, and explicitly stated that their responses were based on such transmitted rulings.

Even scholars capable of deriving rulings through the methodologies of a recognized school would, if they could not find a clear verdict from the great imams, issue a response based on that school’s legal framework—only with great care.

Lesser scholars, who have not reached such heights, must confine themselves to relaying and transmitting the preferred and necessary rulings of their own legal school.

This is the duty of every mufti who is not qualified for ijtihad. They must convey the established positions of the school they follow.

Within the Hanafi madhab, for example, a mufti should first seek a ruling from the zahir al-riwaya books attributed to Imam al-Azam. If none is found, he may give a fatwa based on the words of Imam Abu Yusuf. If his view is unavailable, then Imam Muhammad’s. And if any opinion from these imams has been favored by scholars due to the needs of the time, the mufti should adopt that opinion.

From all this, it becomes clear that issuing a fatwa—arriving at a legal verdict—is a most serious undertaking. Not everyone is fit to engage in it. To do so without proper qualification is to trifle with religion.

Commanding the good and forbidding the wrong is a duty upon every Muslim. Yet even this obligation has conditions. Those who lack the necessary qualities are not permitted to carry it out.

Imagine a council of individuals with knowledge in various fields such as medicine, mathematics, literature, and philosophy. If one among them, lacking expertise, begins to offer rulings in medicine or mathematics, would he not be overstepping his bounds and exposing his own ignorance? So how can religious sciences—more delicate and comprehensive than any other—be treated with less care? Who may speak on matters of law, theology, and ethics, which span thousands of intricate issues, without the proper training?

Indeed, the spiritual and eternal consequences of such speech must be taken to heart.

Ömer Nasuhi Bilmen (rahmatullahi alayh)